By Alice Feiring

Photo: Krzysztof Duda

Over the last decade, the Republic of Georgia—one of the world's oldest winemaking countries—has become an unlikely darling of the natural wine community. Alice Feiring visits the small hilltop town that's become ground zero for the rebirth of traditional Georgian winemaking.

When I told people that I was traveling to Georgia to learn more about their wine, the response was, invariably, a look of confusion. “Are there vineyards near Atlanta?”

“The country of,” I’d say. Then I’d clarify, “Bordered by the Caucasus mountain range, not the Blue Ridge.”

“Really? They make wine there?”

Not only do they make it, their wines have become improbable darlings in the natural wine world. But even more to the point, this area east of the Black Sea might be the oldest wine region on the planet. One particular grape seed that is now in the hands of the Georgian National Museum—carbon dated to be between 6,000 and 8,000 years old—might support that claim. The Georgians also have the longest unbroken tradition of vinifying in citron-shaped ceramic amphora they call qvevri, recently recognized by UNESCO as part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. This kind of winemaking, with limited handling and no additives, has survived centuries of marauding invasions, including the devastation of Soviet rule. During those dark years, the use of qvevri almost died out, and with it the people with the knowledge of how to use them.

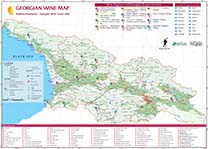

My first visit to Georgia was in 2011 when the wine revival—spurred by an influx of government grants for promotion and development—was in full swing. At at that point there were only about ten commercial wineries committed to both native varieties (Georgia is home to more than 550, with rkatsiteli and saperavi being the two best-known) and traditional techniques. Today, that number has swelled to about 30, giving birth to an unlikely uptick in international wine tourism in a country still so remote it requires complicated air travel. Front and center of the boom: a small hilltop town of about 2,000 residents called Sighnaghi.

It might be only 113 km southeast of Tbilisi (Georgia’s capital), but on shoddy roads, getting there takes nearly two hours. The scenery is rustic-bucolic with a littering of stalls selling cheese and bread—some displaying swinging freshly butchered animal heads and torsos—while live sheep, goats and cows are the source of nearly all traffic jams. But the adorable 18th-century town of Sighnaghi—which miraculously survived a post-Soviet redo with its identity intact—rewards the voyage.

While Georgia’s wine industry is being reborn in regions forgotten during Soviet rule, like Guria and Ateni, Sighnaghi’s growth is unique within the country; the town’s swift rise in winemaking is not the product of government-sponsored grants or incentives for farmers, but something completely grassroots—born of a passion for Georgia’s ancient winemaking rituals and a modern entrepreneurial spirit.

There’s just enough luxe to make it comfy and just enough grit to keep it from having that tourist-town patina. In just a year since I last visited, the town has gained a fancy hotel (serving Prévost champagne, no less), two wine bars, a fledging cidery and three wineries ready to receive visitors. All are within a ten-minute walk of one another.

In a remote town better known for its craftsmen and trading than winemaking, one can’t help but ask: Why Sighnaghi? And why now? Strange as it may sound, it all seems to link back to an ex-pat from Virginia named John Wurdeman, a man who’s managed to build an unofficial wine commune at the crossroads of Europe and Asia.

With the look of a romantic Norse king, the burly 38-year-old artist moved to Georgia after studying painting in Moscow in the 1990s. He fell in love with the country, Georgian folk music, Sighnaghi, Georgian Orthodoxy, his wife Ketevan and wine—in that order. He partnered with farmer and winemaker Gela Patashivili and, in 2007, they started Pheasant’s Tears winery in nearby Tibani. (Their new winery and tasting room, about 20 minutes by horse or car from Sighnaghi, will be open in Spring 2015.)

Pheasant’s Tears quickly made a name for itself both in Georgia and in the export markets for wines that adhered to tradition without sacrificing purity and refinement—a rarity during a time when the country’s winemaking was flirting with international conformity. By 2008, he’d opened the Pheasant’s Tears restaurant and wine bar. It soon became—thanks in part to John’s bilingual skills—a destination for travelers looking to discover the folk music, food and wine of Georgia. The winery itself has also become a Eurasian destination for young people interested in wine—or as they call it, ghvino. Some have come with no background in wine production, while others, like Camille Lapierre from the Domaine Lapierre in Beaujolais, have a lineage. Wurdeman’s magic, and Sighnaghi’s growth, seem to be rooted in his ability toinspire talent to stay.

Case in point? Three years back Paul Rodzianko, a businessman with wine connections and Georgian roots sent his son Alexander to study at the winery. Basically the idea was, “Okay, kid, you want to drop out of college? Learn some skills.”

From the start Alex felt that he wasn’t going back home to Tuxedo Park, New York. “John put a wild and creative idea in my head,” Alex, now 23, said to me while punching down his new vintage in the barely finished (and by the town’s standards) flashy, fully equipped winery. “He said my father and I should partner in making wine and settle down in Sighnaghi. Next thing I know, we were looking at properties for a house and vineyards.”

The newest of Wurdeman’s protégés, Nathan Moss, an audio-visual professional from the UK, was contemplating a new career when he met John through a family member. Shortly after, he bought a one-way ticket to Georgia.

“I knew I would stay,” he says. “This feels like an ancient frontier. Forgotten promised lands.” The only thing he missed was hard cider. Borrowing from Georgia’s winemaking traditions, he’s buried two qvevri and is now foraging for apples.

But Sighnaghi is not solely an ex-patriot outpost. There are natives—like John Okrashivili, who grew up with Wurdeman’s wife and now bottles under the Okro label, and Archil Natsvlishvili, his cousin by marriage and owner of Kerovani—that are also firmly rooted within the Wurdeman clan.

While Georgia’s wine industry is being reborn in regions forgotten during Soviet rule, like Guria and Ateni, Sighnaghi’s growth is unique within the country; the town’s swift rise in winemaking is not the product of government-sponsored grants or incentives for farmers, but something completely grassroots—born of a passion for Georgia’s ancient winemaking rituals and a modern entrepreneurial spirit.

Wurdeman insists that creating some sort of Sighnaghi utopia was really never his master plan, but he does admit to hoping that this pretty town—with its view of the purple mountains in the distance—might evolve into a laboratory for natural wine and spirit development, unique in Georgia and the world. After which he smiles, slyly, and says, “You know, Alice, there’s a house for sale in town. For $20,000 you could…”

© punchdrink.com