by Radka Slovackova

Georgia is the place where monks and some winemakers alike still bury wine-to-be under the ground in ancient vessels called ‘qvevri’. These pitchers resemble amphora with their shape and material from which they are made of – the clay. Everything goes inside the quevri – grapes with skins, stalks, grape stone. Grapes ferment on its natural yeast and later mature into full-bodied wine in qvevri hermetically closed and buried under the ground. This aging process takes usually about 5-6 months leading to full-bodied and highly tannic wines (long contact with skins and stalks releases more tannins into wine). Such description might sound a bit detracting, yet these wines are velvety, intense and if made by conscious producers also surprisingly very well-balanced.

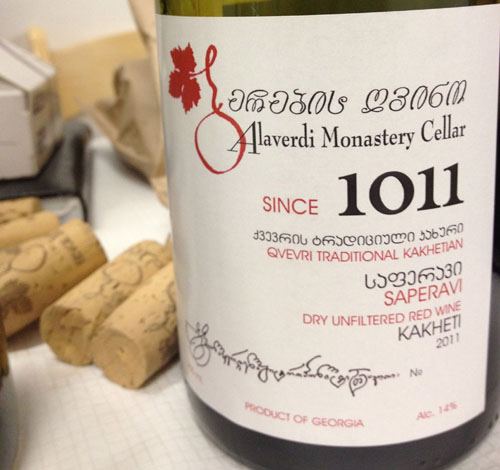

Experience often bears success. That is particularly true about Georgian monks making wines for over 10 centuries at Alaverdi monastery in Kakheti, eastern dry region on the foothills of Caucasus mountain range. Since the year 1011 (what a number!) they have been making wines for royalty including Russian tsars. They are proud of their heritage and believe that winemaking once begun here in Georgia. Numerous archeological findings seem to support Georgia’s claim of pioneering wine production thousands years ago. Whether Georgia or precisely the geographical location the country occupies today was the first remains a mystery, nevertheless the tradition of making wine reaches as far as our knowledge of documented history, so its people must know how to do it. That is perhaps why, even though still using pre-classical methods, the wines are mostly balanced and very interesting. It is their unique taste that enchanted me – I do not know any white or red wine tasting at least closely to the wines I tried so far.

It seems that the most promising from the over 500 grape varietals grown in Georgia is the red Saperavi. Its high tannic content and acidity promises long aging and I would recommend to drink the wines after a couple of years in bottle. Whether used in blends or on its own, often unfiltered as aging in qvevri brings clear wines, it rewards your palate with an intense aroma of violets, plums and spices and velvety tannins if drunk older. As I said there is now wine like this, but if I had to compare it to well-known varietals I would say its taste resembles something between Shiraz and Pinot Noir.

Winemaking as elsewhere differs from producer to producer and wine to wine. One maker can produce wine with as well as without skin contact to reduce the sharp tannins. Iago Bitarishvili makes both so you can taste them and decide what you prefer. Trying dry white Chinuri in both versions shocked me how different the wine can taste! Without skin contact the wine was quite mineral and had aromas of green hazelnuts and touch of petrol. Very interesting wine, yet I slightly preferred Iago’s Chinuri made with skin contact. Its deeper yellow color distinguishes it from the previous. Petrol was still present on the palate as well as on the nose, yet candied and ripe fruits balanced by mineral wet stones both revealed higher ripeness of grapes during harvest necessary for maturation on skins and the character of the mineral soil. Grown in Kakheti region in Mukhrani valley, there are only about 3.000 bottles of this wine produced by Iago Bitarishvili depending on the year.

Despite the fact that Saperavi is the most celebrated local grape, I was beguiled by some of the white wines. The Chinuri was one of them, but my favorite was Rkatsitelli matured with skins in qvevris (clay jars). Twin brothers Gela and Gia Gamtkitsulashvili made in 2010 a lovely yet deceiving dry wine from Rkatsitelli. It is a chameleon with jammy, compote and concentration suggesting nose, while on the palate it is an aromatic wine with cloves and warm spices characteristic for this white varietal.

From other indigenous Georgian white varietals spicy and meaty Kisi from Alaverdi monastery is noteworthy. I know it is a very personal description but it smells and tastes like my grandmother’s spicy wurst (thick sausage). Just imagine some pork, spicy paprika, smoke and there you are. Its natural high acidity, intense aroma and tannins from skins suggest its aging potential, so if you ever manage to visit the monastery get a case or more as you can relish this wine in five and even more years.

The Georgian wines are highly promising, nevertheless, there remind a number of challenges – political and logistic to name a few, for the country becoming a world-known and accessible wine-producing region competing with the like of Croatia or Lebanon. Hopefully, the insatiable curiosity of some wine consumers and steady quality of local production will deliver Georgia recognition it deserves.

NOTE: I have tasted all the above mentioned wines during London’s Real Wine Fair and International Wine Fair in May 2012. All the above mentioned wines can be classified as ‘natural’ since there are no additives, no filtration and overall minimum manipulation during the production. Although, the term natural wine still remains controversial and subject of heated debates in the world circle of wine experts.

© winebeing.com