by Paul Salopek

Meet Maka Kozhara: a wine expert. Young, intelligent, friendly.

Kozhara sits in an immense cellar in a muddy green valley in the Republic of Georgia. The cellar lies beneath an imitation French chateau. The vineyards outside, planted in gnarled rows, stretch away for miles. Once, in the late 19th century, the chateau’s owner, a Francophile, a vintner and eccentric Georgian aristocrat, pumped barrels of home-brewed champagne through a large outdoor fountain: a golden spray of drinkable bubbles shot into the air.

“It was for a party,” Kozhara says. “He loved wine.”

Kozhara twirls a glass of wine in her hand. She holds the glass up to the ceiling light. She is interrogating a local red—observing what physicists call the Gibbs-Maranoni Effect: How the surface tension of a liquid varies depending on its chemical make-up. It is a diagnostic tool. If small droplets of wine cling to the inside of a glass: the wine is dry, a high-alcohol vintage. If the wine drips sluggishly down the glass surface: a sweeter, less alcoholic nectar. Such faint dribbles are described, among connoisseurs, as the “legs” of a wine. But here in Georgia wines also possess legs of a different kind. Legs that travel. That conquer. That walk out of the Caucasus in the Bronze Age.

The taproots of Georgia’s wine are muscular and very old. They drill down to the bedrock of time, into the deepest vaults of human memory. The earliest settled societies in the world—the empires of the Fertile Crescent, of Mesopotamia, of Egypt, and later of Greece and Rome—probably imported the secrets of viticulture from these remote valleys, these fields, these misty crags of Eurasia. Ancient Georgians famously brewed their wines in clay vats called kvevri. Today, these bulbous amphoras are still manufactured. Vintners still fill them with wine. The pots dot Georgia like gigantic dinosaur eggs. They are under farmers’ homes, in restaurants, in parks, in museums, outside gas stations. Kvevri are a symbol of Georgia: a source of pride, unity, strength. They deserve to appear on the national flag. It has been said that one reason why Georgians never converted en masse to Islam (the Arabs invaded the region in the seventh century) was because of their attachment to wine. Georgians refused to give up drinking.

Kozhara pours me a glass. It is her winery’s finest vintage, ink-dark, dense. The liquid shines in my hand. It exhales an aroma of earthy tannins. It is a scent that is deeply familiar, as old as civilization, that goes immediately to the head.

“Wine”—Kozhara declares flatly—“is our religion.”

To which the only possible response is: Amen.

“We aren’t interested in proving that winemaking was born in Georgia,” insists David Lordkipanidze, the director of the Georgia National Museum, in Tbilisi. “That isn’t our goal. There are much better questions to ask. Why did it start? How did it spread across the ancient world? How do you connect today’s grape varieties to the wild grape? These are the important questions.”

Lordkipanidze oversees a sprawling, multinational, scientific effort to unearth the origins of wine. The Americans have NASA. Iceland has Bjork. But Georgia has the “Research and Popularization of Georgian Grape and Wine Culture” project. Archaeologists and botanists from Georgia, geneticists from Denmark, Carbon-14 dating experts from Israel, and other specialists from the United States, Italy, France and Canada have been collaborating since early 2014 to explore the primordial human entanglements with the grapevine.

Patrick McGovern, a molecular archaeologist from the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and a member of this intellectual posse, calls wine perhaps the most “consequential beverage” in the story of our species.

“Imagine groups of hunter-gatherers meeting for the first time,” McGovern says. “Wine helps to bring people together. It’s social lubrication. Alcohol does this.”

Human beings have been consuming alcohol for so long that 10 percent of the enzymes in our livers have evolved to metabolize it into energy: a sure sign of tippling’s antiquity. The oldest hard evidence of intentional fermentation comes from northern China, where chemical residues in pottery suggest that 9,000 years ago our ancestors quaffed a dawn cocktail of rice, honey and wild fruit.

Grape wines came a bit later. McGovern surmises that their innovation was accidental: wild grapes crushed at the bottom of a container, their juices gone bad, partly digested by airborne yeasts. For thousands of years, the fermentation process remained a mystery. This gave wine its otherworldly power. “You have a mind-altering substance that comes out of nowhere,” McGovern says, “and so this drink starts to feature at the center of our religions. It became embedded in life, in family, in faith. Even the dead started to be buried with wine.”

From the beginning, wine was more than a mere intoxicant. It was an elixir. Its alcohol content and tree resins, added in ancient times as wine preservatives, had anti-bacterial qualities. In ages when sanitation was abysmal, drinking wine—or mixing it with water—reduced disease. Wine saved lives.

“Cultures that made the first wines were productive, rich,” says Mindia Jalabadze, a Georgian archaeologist. “They were growing wheat and barley. They had sheep, pigs, and cattle—they bred them. Life was good. They also hunted and fished.”

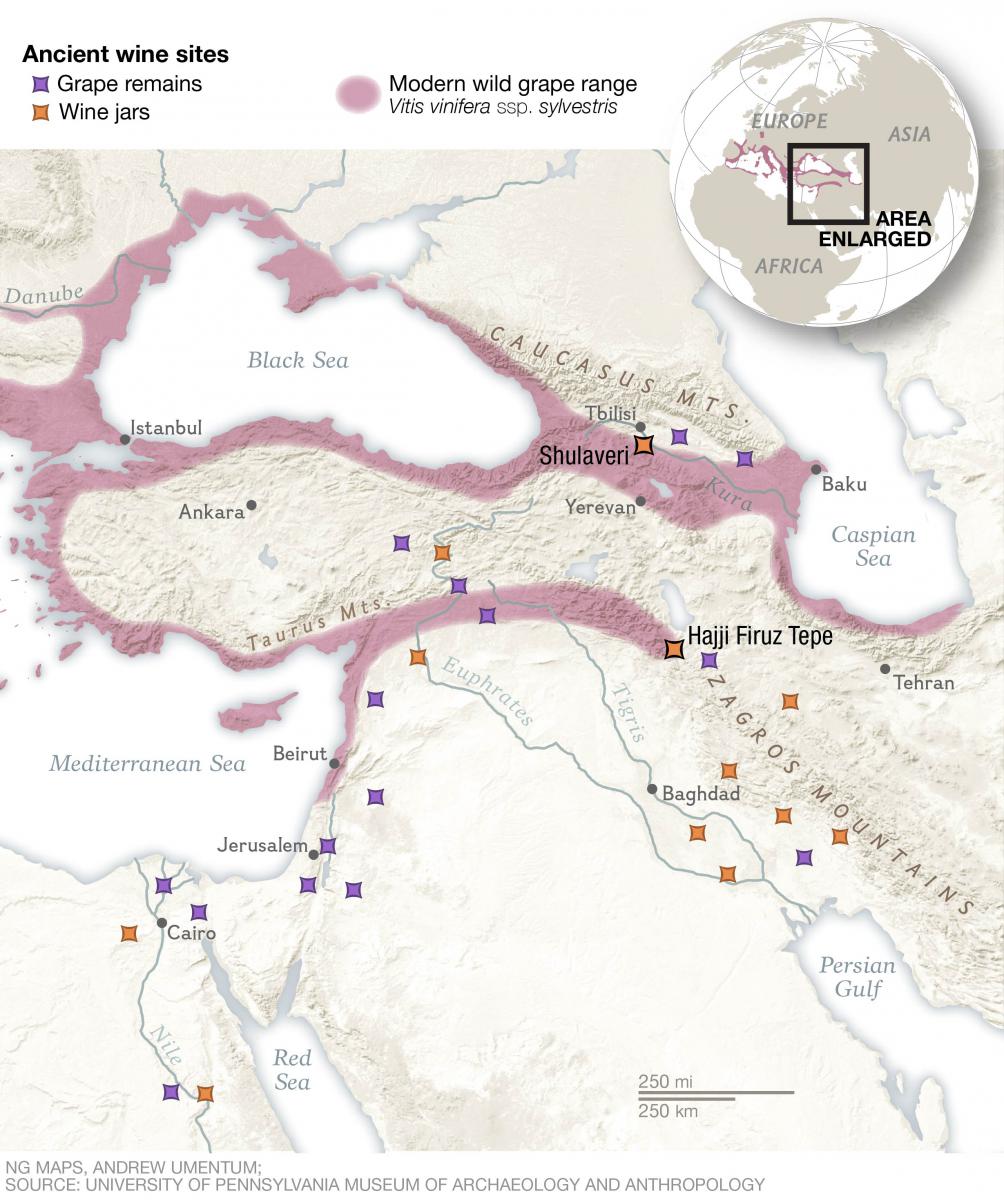

Jalabadze is talking about a Neolithic culture called Shulaveri-Shomu whose mound sites in Georgia arose during a wet cycle in the southern Caucasus and date back to first inklings of agriculture, before the time of metal. The villagers used stone tools, tools of bone. They crafted gigantic pots the size of refrigerators. Such vessels—precursors to the fabled kvevri—held grains and honey, but also wine. How can we know? One such pot is decorated with bunches of grapes. Biochemical analyses of the pottery, carried out by McGovern, shows evidence of tartaric acid, a telltale clue of grape brewing. These artifacts are 8,000 years old. Georgia’s winemaking heritage predates other ancient wine-related finds in Armenia and Iran by centuries. This year, researchers are combing Shulaveri-Shomu sites for prehistoric grape pips.

One day, I visit the remains of a 2,200-year-old Roman town in central Georgia: Dzalisa. The beautiful mosaic floors of a palace are holed, bizarrely pocked, by clay cavities large enough to hold a man. They are kvevri. Medieval Georgians used the archaeological ruins to brew wine. South of Tbilisi, on a rocky mesa above a deep river gorge, lies the oldest hominid find outside Africa: a 1.8-million-year-old repository of hyena dens that contain the skulls of Homo erectus. In the ninth or tenth centuries, workers dug a gigantic kvevri into the site, destroying priceless pre-human bones.

Georgia’s past is punctured by wine. It marinates in tannins.

For more than two years, I have trekked north out of Africa. More than 5,000 years ago, wine marched in the opposite direction, south and west, out of its Caucasus cradle.

“Typical human migrations involved mass slaughter,” says Stephen Batiuk, an archaeologist at the University of Toronto. “You know, migration by the sword. Population replacement. But not the people who brought wine culture with them. They spread out and then lived side-by-side with host cultures. They established symbiotic relationships.”

Batiuk is talking about an iconic diaspora of the classical world: the expansion of Early Trans-Caucasian Culture (ETC), which radiated from the Caucasus into eastern Turkey, Iran, Syria, and the rest of the Levantine world in the third millennium B.C.

Batiuk was struck by a pattern: Distinctive ETC pottery pops up wherever grape cultivation occurs.

“These migrants seemed to be using wine technology as their contribution to society,” he says. “They weren’t ‘taking my job.’ They were showing up with seeds or grape cuttings and bringing a new job—viticulture, or at least refinements to viticulture. They were an additive element. They sort of democratized wine. Wherever they go, you see an explosion of wine goblets.”

ETC pottery endured as a distinctive archaeological signature for 700 to 1,000 years after leaving the Caucasus. This boggles experts such as Batiuk. Most immigrant cultures become integrated, absorbed, and vanish after just three generations. But there is no mystery here.

On a pine-stubbled mountain above Tbilisi, a man named Beka Gotsadze home-brews wine in a shed outside his house.

Gotsadze: big, affable, red-faced. His is one of tens of thousands of ordinary Georgian families who still squeeze magic from Vitis vinifera for their own enjoyment. He uses clay kvevri buried in the earth; the hill under his house is his incubator. He pipes coils of household tap water around the jars to control the fermentation. He employs no chemicals, no additives. His wines steep in the darkness the way Georgian wine always has: the grapes mashed together with their skins, their stems.

Gotsadze says, “You put it in the ground and ask God: ‘Will this batch be good?’”

He says: “Every wine producer is giving you his heart. My kids help me. They are giving you their hearts. The bacteria that ferment? They came on the wind! The clouds? They are in there. The sun is in there. The wine holds everything!”

Gotsadze took his family’s wines to a competition in Italy once, to be judged. “The judge was amazed. He said, ‘Where have you been hiding all this time?’ I said, ‘Sorry, you know, but we’ve been a little busy over here, fighting the Russians!’”

And at his raucous dinner table, a forest of stemmed glasses holds the dregs of tavkveri rosé, chinuri whites, saperavis reds. The eternal ETC thumbprint is there.

© outofedenwalk.nationalgeographic.com