- Posted on Tue, 02/05/2013 - 11:29

By Giorgi Barisashvili

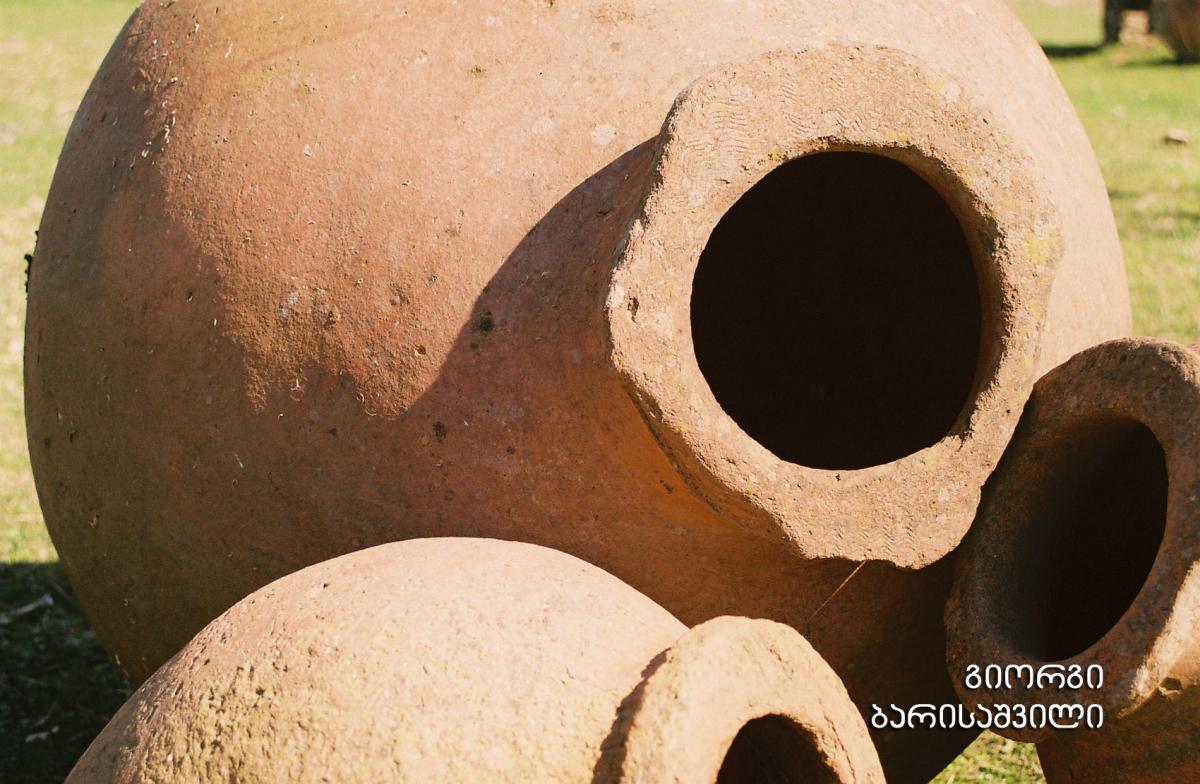

A qvevri lid is decisive for durable, airtight and quality storage. It can be made of wood, generally found in West Georgia, or stone, which is more popular in East Georgia, especially in Kakheti. Indeed there were several villages known for their skill in manufacturing qvevri lids. One such village was Sabue in the Kvareli district, though qvevri lids are no longer made there today.

Stone qvevri lids made of slate mined on the slopes of the Greater Caucasus were frequently used in East Georgia. Lids can also be made of other types of rock. Every stone isn’t suitable for the purpose since some are prone to mold which can affect wine quality. The same qvevri washing and sanitation requirements apply equally to lids, which must be washed as thoroughly as the qvevri itself.

In West Georgian areas such as Imereti, qvevri lids are called orgo or badimi and are made of wood. These are specifically created from lime (linden), chestnut and oak timber. The qvevri lid most popular in West Georgia is divided in two parts with a hole in the middle to release the carbon dioxide that develops during alcoholic fermentation. The qvevris were lidded during this fermentation process and a “windpipe” was attached to the hole on the lid, and covered with a piece of gauze or other cloth to prevent insects or dirt falling into the qvevri. Then yellow earth was packed around it.

Orgolids made of oak or chestnut wood must first of all be soaked in hot water to remove their bitterness and “coarse” substances characteristic of the timber, which might affect wine quality. The wooden lids of large qvevris used to be made of even more than two parts.

The practice of qvevri lidding remains a challenging issue, as proper lidding is a necessary prerequisite for a qvevri wine’s durable and safe storage. In East and West Georgia qvevri lidding procedures differ just as the lids themselves are different. In West Georgia, lids are placed directly on the opening of the buried qvevri (churi) then covered over with special yellow earth. Thereafter, the yellow earth is thoroughly packed down with a special implement called a kvezho planed out of a log.A mound of common earth is then added.

In Kakheti, East Georgia, the process is different: hand-mixed clay is applied first to the qvevri opening which has to be completely dry so this clay will stick to it well.Then the clay is covered with a stone lid which is strongly pressed into the clay, sealing the qvevri hermetically.

The clay, mixed with potable water, should also contain a small amount of sulfuric anhydride to disinfect the water and the clay.Once the clay on the qvevri opening sets and becomes hard, a burning sulfur wick is fixed sideways into the clay with the wick inwards.When the sulfur wick is kindled, the qvevri is then lidded and sealed. Gradually the air space between the wine and the qvevri lid fills with sulfur smoke which then cools and forms a vacuum. This process is a necessary prerequisite for durable and airtight storage, however the technique is not used in West Georgia. Also in East Georgia, particularly in Kakheti, the lidded qvevri is covered with an earthen mound that is regularly dampened with water, especially important in summer.

From: Making Wine in Qvevri: a Unique Georgian Tradition, Tb. 2011.

© elkana

Tagged: