By Andrew Jefford

In Georgia, winemaking methods that were developed 8,000 years ago have not been abandoned but remain best practice

You could call it a great unlearning. Sixty years of technical mastery over raw materials have led, in the view of some wine producers, to a loss of the innate differences with which wine was once synonymous. How, though, to beat a retreat? “Natural” wine (made without additives) and “orange” wine (white wine made like red, by lengthy soaking of skins with juice) have been two of the most radical solutions. Classically trained palates often consider the results grotesque; younger drinkers find them fun. They’re now a kind of punk wine – a disconcerting alternative to the mainstream, inspiring two separate London wine shows each spring and even threading their impolite way through the Michelin stars.

Much of the running for this movement has been made in Italy, inspired by the contadini (peasant farmers) who never bothered much with additives anyway, nor saw the point of treating white grapes differently from red. The movement’s leaders, though, look further east, to Georgia, which is wine’s Jerusalem; tributes and pilgrimages abound. Georgia’s winemakers regard this as both gratifying and discomfiting.

Georgia is a land of multiple wine astonishments. Archaeologists are unsure whether wine’s birthplace was in southern Anatolia or Transcaucasia; what is beyond doubt, though, is that Georgia is the only country in the world where winemaking methods that were developed up to 8,000 years ago have not only never been abandoned but remain in many ways best practice. Georgia’s winemakers are the guardians of wine’s oldest traditions, and they’re happy that this is now both recognised and respected. The discomfort comes because they have learnt their considerable refinement and subtlety through thousands of vintages; much of this refinement is absent in the hit-and-miss natural-wine noise generated elsewhere.

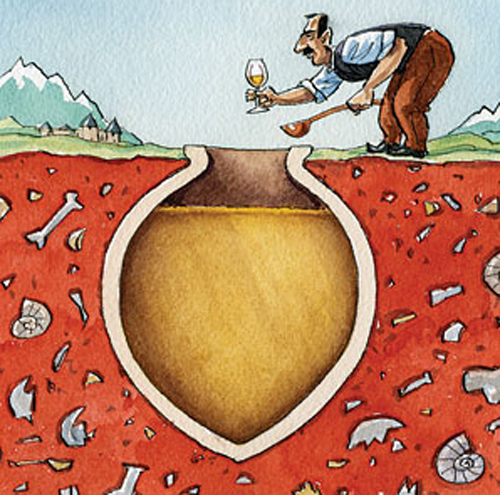

There are two compelling reasons to seek out Georgian wine. The first is its repertoire of indigenous grape varieties: 525 survive, out of a total thought to have once numbered 1,400 or more. The second is, precisely, those old ways – the chance to taste wines that have been fermented in the buried, wax-lined clay jars the Georgians call qvevri. Both red and white wines can be made in these beautiful, maternally contoured vessels, whose size varies from flask-like to bear-sized. (Human skeletons have been found, in contented repose, within ancient jars.) In essence, red wines made in qvevri don’t differ dramatically from “normal” red wines, which also ferment with their skins and pips, and sometimes their stalks too. Red wines made in qvevri, moreover, are often removed from the jars after fermentation for wood ageing, or for returning to a clean qvevri. This too mimics normal red-wine practice.

White wines made in this way, by contrast, are utterly different from conventional white wines. The Georgians call them “golden” rather than “orange”, and they spend a full six months with skins and pips, as well as undergoing their entire fermentative cycle in contact with those materials and with the copious yeast deposits the cycle produces. The only external addition is, in most cases, a little sulphur after fermentation. The jars are then sealed and earth-covered for the ageing process. The result is a width, a tannic grip and a textural depth that no conventionally made white wine will ever have. The wines’ aromas and flavours are singular too. Their acidity is muted, since they have all been through the acid-softening malolactic fermentation, while contact with the other matter in the jar, especially the yeast deposits, rounds the flavours further. In place of the fresh fruits that so many white wines suggest, these evoke dried fruits, mushrooms, straw, nuts and umami. They have less of an oxidative tang than their colours suggest; indeed, their articulation is often understated and quiet, though orchestral in its allusive range. They are meditative wines, sumptuous and subtle.

Not every Georgian wine, of course, is made in buried clay jars; the majority are made conventionally, and it is in these wines that Georgia’s indigenous grape varieties can be appreciated most clearly, at least by palates unused to the thickening intrigue of the qvevri. The country may have a huge patrimony of varieties, but a few stand out for their quality.

The red variety Saperavi is the most commanding. It is deeply coloured (the name means “dye”) and no less prodigious in almost every dimension, with astonishing energetic force in the mouth. A great Saperavi is shockingly good: no other words will do. The variety also blends well (with Bordeaux varieties Cabernet and Merlot, for instance) and is ideal for making the semi-sweet reds so popular in Russia. Other Georgian red varieties of note include the lighter Tavkveri and the fresh-flavoured Shavkapito, but Saperavi is the grandee.

There are, by contrast, at least three great indigenous Georgian white varieties. Rkatsiteli is the best known (its planting outside Georgia’s borders, in Ukraine, Moldova and Bulgaria, helps to make it the world’s fifth most planted white grape variety). Like Chardonnay, its style varies considerably with location and producer intent, but fragrance, vinosity, a crisp balance and a complex allusive repertoire are all possible.

My own favourite among Georgian white varieties is the subtle, hauntingly aromatic Mtsvane, a kind of Caucasian cousin of Rhône whites such as Marsanne, Roussanne or Viognier. Kisi is the third leading white variety, said to be floral and fresh, though the examples I tried were full-bodied and rich.

There are further nuances, as you’d expect from an 8,000-year-old tradition, including regional differences and a series of village “appellations” which imply particular blends of varieties. They all reinforce Georgia’s message to the curious, though, which is that wine, great wine, is still more intriguingly diverse and more strangely beautiful than we thought.

Andrew’s Picks

Georgian fine-wine producers:

• Alaverdi Monastery

• Besini

• Khareba

• Maisuradze

• Ch Mukhrani

• Pheasant’s Tears

• Vinoterra/Schuchmann

• Wine Man

• Winiveria

© THE FINANCIAL TIMES LTD